| Main Index | Next Part |

Professor Maspero does not need to be introduced to us. His name is well known in England and America as that of one of the chief masters of Egyptian science as well as of ancient Oriental history and archaeology. Alike as a philologist, a historian, and an archaeologist, he occupies a foremost place in the annals of modern knowledge and research. He possesses that quick apprehension and fertility of resource without which the decipherment of ancient texts is impossible, and he also possesses a sympathy with the past and a power of realizing it which are indispensable if we would picture it aright. His intimate acquaintance with Egypt and its literature, and the opportunities of discovery afforded him by his position for several years as director of the Bulaq Museum, give him an unique claim to speak with authority on the history of the valley of the Nile. In the present work he has been prodigal of his abundant stores of learning and knowledge, and it may therefore be regarded as the most complete account of ancient Egypt that has ever yet been published.

In the case of Babylonia and Assyria he no longer, it is true, speaks at first hand. But he has thoroughly studied the latest and best authorities on the subject, and has weighed their statements with the judgment which comes from an exhaustive acquaintance with a similar department of knowledge.

Naturally, in progressive studies like those of Egyptology and Assyriology, a good many theories and conclusions must be tentative and provisional only. Discovery crowds so quickly on discovery, that the truth of to-day is often apt to be modified or amplified by the truth of to-morrow. A single fresh fact may throw a wholly new and unexpected light upon the results we have already gained, and cause them to assume a somewhat changed aspect. But this is what must happen in all sciences in which there is a healthy growth, and archaeological science is no exception to the rule.

The spelling of ancient Egyptian proper names adopted by Professor Maspero will perhaps seem strange to many. But it must be remembered that all our attempts to represent the pronunciation of ancient Egyptian words can be approximate only; we can never ascertain with certainty how they were actually sounded. All that can be done is to determine what pronunciation was assigned to them in the Greek period, and to work backwards from this, so far as it is possible, to more remote ages. This is what Professor Maspero has done, and it must be no slight satisfaction to him to find that on the whole his system of transliteration is confirmed by the cuneiform tablets of Tel el-Amarna.

The difficulties attaching to the spelling of Assyrian names are different from those which beset our attempts to reproduce, even approximately, the names of ancient Egypt. The cuneiform system of writing was syllabic, each character denoting a syllable, so that we know what were the vowels in a proper name as well as the consonants. Moreover, the pronunciation of the consonants resembled that of the Hebrew consonants, the transliteration of which has long since become conventional. When, therefore, an Assyrian or Babylonian name is written phonetically, its correct transliteration is not often a matter of question. But, unfortunately, the names are not always written phonetically. The cuneiform script was an inheritance from the non-Semitic predecessors of the Semites in Babylonia, and in this script the characters represented words as well as sounds. Not unfrequently the Semitic Assyrians continued to write a name in the old Sumerian way instead of spelling it phonetically, the result being that we do not know how it was pronounced in their own language. The name of the Chaldæan Noab, for instance, is written with two characters which ideographically signify "the sun" or "day of life," and of the first of which the Sumerian values were ut, babar, khis, tarn, and par, while the second had the value of zi. Were it not that the Chaldæan historian Bêrôssos writes the name Xisuthros, we should have no clue to its Semitic pronunciation.

Professor Maspero's learning and indefatigable industry are well known to me, but I confess I was not prepared for the exhaustive acquaintance he shows with Assyriological literature. Nothing seems to have escaped his notice. Papers and books just published, and half forgotten articles in obscure periodicals which appeared years ago, have all alike been used and quoted by him. Naturally, however, there are some points on which I should be inclined to differ from the conclusions he draws, or to which he has been led by other Assyriologists. Without being an Assyriologist himself, it was impossible for him to be acquainted with that portion of the evidence on certain disputed questions which is only to be found in still unpublished or untranslated inscriptions.

There are two points which seem to me of sufficient importance to justify my expression of dissent from his views. These are the geographical situation of the land of Magan, and the historical character of the annals of Sargon of Accad. The evidence about Magan is very clear. Magan is usually associated with the country of Melukhkha, "the salt" desert, and in every text in which its geographical position is indicated it is placed in the immediate vicinity of Egypt. Thus Assur-bani-pal, after stating that he had "gone to the lands of Magan and Melukhkha," goes on to say that he "directed his road to Egypt and Kush," and then describes the first of his Egyptian campaigns. Similar testimony is borne by Esar-haddon. The latter king tells us that after quitting Egypt he directed his road to the land of Melukhkha, a desert region in which there were no rivers, and which extended "to the city of Rapikh" (the modern Raphia) "at the edge of the wadi of Egypt" (the present Wadi El-Arîsh). After this he received camels from the king of the Arabs, and made his way to the land and city of Magan. The Tel el-Amarna tablets enable us to carry the record back to the fifteenth century b.c. In certain of the tablets now as Berlin (Winckler and Abel, 42 and 45) the Phoenician governor of the Pharaoh asks that help should be sent him from Melukhkha and Egypt: "The king should hear the words of his servant, and send ten men of the country of Melukhkha and twenty men of the country of Egypt to defend the city [of Gebal] for the king." And again, "I have sent [to] Pharaoh" (literally, "the great house") "for a garrison of men from the country of Melukhkha, and... the king has just despatched a garrison [from] the country of Melukhkha." At a still earlier date we have indications that Melukhkha and Magan denoted the same region of the world. In an old Babylonian geographical list which belongs to the early days of Chaldsean history, Magan is described as "the country of bronze," and Melukhkha as "the country of the samdu," or "malachite." It was this list which originally led Oppert, Lenormant, and myself independently to the conviction that Magan was to be looked for in the Sinaitic Peninsula. Magan included, however, the Midian of Scripture, and the city of Magan, called Makkan in Semitic Assyrian, is probably the Makna of classical geography, now represented by the ruins of Mukna.

As I have always maintained the historical character of the annals of Sargon of Accad, long before recent discoveries led Professor Hilprecht and others to adopt the same view, it is as well to state why I consider them worthy of credit. In themselves the annals contain nothing improbable; indeed, what might seem the most unlikely portion of them—that which describes the extension of Sargon's empire to the shores of the Mediterranean—has been confirmed by the progress of research. Ammi-satana, a king of the first dynasty of Babylon (about 2200 B.C.), calls himself "king of the country of the Amorites," and the Tel el-Amarna tablets have revealed to us how deep and long-lasting Babylonian influence must have been throughout Western Asia. Moreover, the vase described by Professor Maspero in the present work proves that the expedition of Naram-Sin against Magan was an historical reality, and such an expedition was only possible if "the land of the Amorites," the Syria and Palestine of later days, had been secured in the rear. But what chiefly led me to the belief that the annals are a document contemporaneous with the events narrated in them, are two facts which do not seem to have been sufficiently considered. On the one side, while the annals of Sargon are given in full, those of his son Naram-Sin break off abruptly in the early part of his reign. I see no explanation of this, except that they were composed while Naram-Sin was still on the throne. On the other side, the campaigns of the two monarchs are coupled with the astrological phenomena on which the success of the campaigns was supposed to depend. We know that the Babylonians were given to the practice and study of astrology from the earliest days of their history; we know also that even in the time of the later Assyrian monarchy it was still customary for the general in the field to be accompanied by the asipu, or "prophet," the ashshâph of Dan. ii. 10, on whose interpretation of the signs of heaven the movements of the army depended; and in the infancy of Chaldæn history we should accordingly expect to find the astrological sign recorded along with the event with which it was bound up. At a subsequent period the sign and the event were separated from one another in literature, and had the annals of Sargon been a later compilation, in their case also the separation would assuredly have been made. That, on the contrary, the annals have the form which they could have assumed and ought to have assumed only at the beginning of contemporaneous Babylonian history, is to me a strong testimony in favour of their genuineness.

It may be added that Babylonian seal-cylinders have been found in Cyprus, one of which is of the age of Sargon of Accad, its style and workmanship being the same as that of the cylinder figured in vol. iii. p. 96, while the other, though of later date, belonged to a person who describes himself as "the servant of the deified Naram-Sin." Such cylinders may, of course, have been brought to the island in later times; but when we remember that a characteristic object of prehistoric Cypriote art is an imitation of the seal-cylinder of Chaldsea, their discovery cannot be wholly an accident.

Professor Maspero has brought his facts up to so recent a date that there is very little to add to what he has written. Since his manuscript was in type, however, a few additions have been made to our Assyriological knowledge. A fresh examination of the Babylonian dynastic tablet has led Professor Delitzsch to make some alterations in the published account of what Professor Maspero calls the ninth dynasty. According to Professor Delitzsch, the number of kings composing the dynasty is stated on the tablet to be twenty-one, and not thirty-one as was formerly read, and the number of lost lines exactly corresponds with this figure. The first of the kings reigned thirty-six years, and he had a predecessor belonging to the previous dynasty whose name has been lost. There would consequently have been two Elamite usurpers instead of one.

I would further draw attention to an interesting text, published by Mr. Strong in the Babylonian and Oriental Record, which I believe to contain the name of a king who belonged to the legendary dynasties of Chaldæa. This is Samas-natsir, who is coupled with Sargon of Accad and other early monarchs in one of the lists. The legend, if I interpret it rightly, states that "Elam shall be altogether given to Samas-natsir;" and the same prince is further described as building Nippur and Dur-ilu, as King of Babylon and as conqueror both of a certain Baldakha and of Khumba-sitir, "the king of the cedar-forest." It will be remembered that in the Epic of Gil-games, Khumbaba also is stated to have been the lord of the "cedar-forest."

But of new discoveries and facts there is a constant supply, and it is impossible for the historian to keep pace with them. Even while the sheets of his work are passing through the press, the excavator, the explorer, and the decipherer are adding to our previous stores of knowledge. In Egypt, Mr. de Morgan's unwearied energy has raised as it were out of the ground, at Kom Ombo, a vast and splendidly preserved temple, of whose existence we had hardly dreamed; has discovered twelfth-dynasty jewellery at Dahshur of the most exquisite workmanship, and at Meir and Assiut has found in tombs of the sixth dynasty painted models of the trades and professions of the day, as well as fighting battalions of soldiers, which, for freshness and lifelike reality, contrast favourably with the models which come from India to-day. In Babylonia, the American Expedition, under Mr. Haines, has at Niffer unearthed monuments of older date than those of Sargon of Accad. Nor must I forget to mention the lotiform column found by Mr. de Morgan in a tomb of the Old Empire at Abusir, or the interesting discovery made by Mr. Arthur Evans of seals and other objects from the prehistoric sites of Krete and other parts of the AEgean, inscribed with hieroglyphic characters which reveal a new system of writing that must at one time have existed by the side of the Hittite hieroglyphs, and may have had its origin in the influence exercised by Egypt on the peoples of the Mediterranean in the age of the twelfth dynasty.

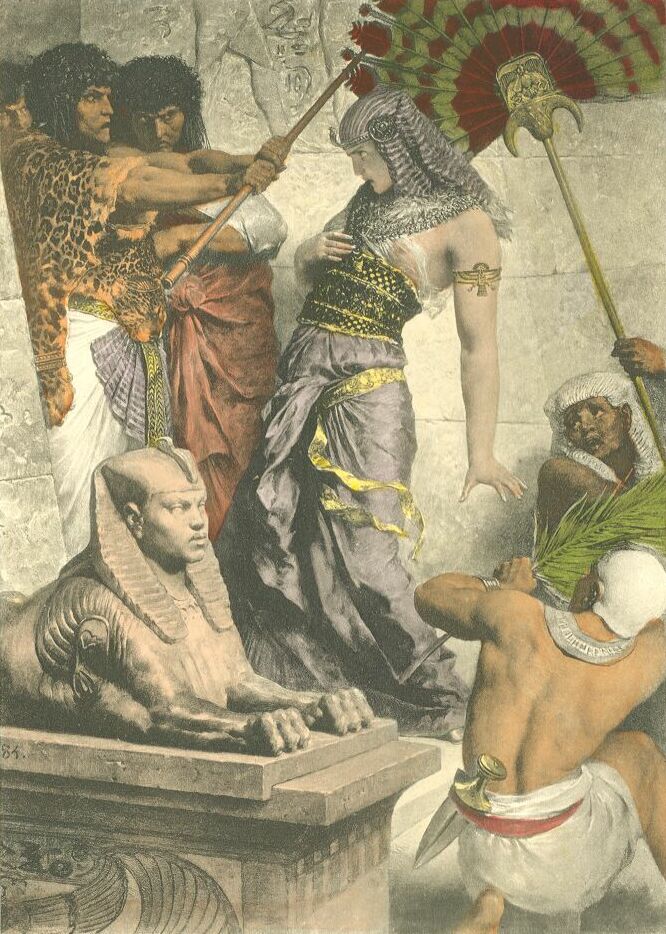

In volumes IV., V., and VI. we find ourselves in the full light of an advanced culture. The nations of the ancient East are no longer each pursuing an isolated existence, and separately developing the seeds of civilization and culture on the banks of the Euphrates and the Nile. Asia and Africa have met in mortal combat. Babylonia has carried its empire to the frontiers of Egypt, and Egypt itself has been held in bondage by the Hyksôs strangers from Asia. In return, Egypt has driven back the wave of invasion to the borders of Mesopotamia, has substituted an empire of its own in Syria for that of the Babylonians, and has forced the Babylonian king to treat with its Pharaoh on equal terms. In the track of war and diplomacy have come trade and commerce; Western Asia is covered with roads, along which the merchant and the courier travel incessantly, and the whole civilised world of the Orient is knit together in a common literary culture and common commercial interests.

The age of isolation has thus been succeeded by an age of intercourse, partly military and antagonistic, partly literary and peaceful. Professor Maspero paints for us this age of intercourse, describes its rise and character, its decline and fall. For the unity of Eastern civilization was again shattered. The Hittites descended from the ranges of the Taurus upon the Egyptian province of Northern Syria, and cut off the Semites of the west from those of the east. The Israelites poured over the Jordan out of Edom and Moab, and took possession of Canaan, while Babylonia itself, for so many centuries the ruling power of the Oriental world, had to make way for its upstart rival Assyria. The old imperial powers were exhausted and played out, and it needed time before the new forces which were to take their place could acquire sufficient strength for their work.

As usual, Professor Maspero has been careful to embody in his history the very latest discoveries and information. Notice, it will be found, has been taken even of the stela of Meneptah, recently disinterred by Professor Pétrie, on which the name of the Israelites is engraved. At Elephantine, I found, a short time since, on a granite boulder, an inscription of Khufuânkh—whose sarcophagus of red granite is one of the most beautiful objects in the Gizeh Museum—which carries back the history of the island to the age of the pyramid-builders of the fourth dynasty. The boulder was subsequently concealed under the southern side of the city-wall, and as fragments of inscribed papyrus coeval with the sixth dynasty have been discovered in the immediate neighbourhood, on one of which mention is made of "this domain" of Pepi II., it would seem that the town of Elephantine must have been founded between the period of the fourth dynasty and that of the sixth. Manetho is therefore justified in making the fifth and sixth dynasties of Elephantine origin.

It is in Babylonia, however, that the most startling discoveries have been made. At Tello, M. de Sarzec has found a library of more than thirty thousand tablets, all neatly arranged, piled in order one on the other, and belonging to the age of Gudea (b.c. 2700). Many more tablets of an early date have been unearthed at Abu-Habba (Sippara) and Jokha (Isin) by Dr. Scheil, working for the Turkish government. But the most important finds have been at Niffer, the ancient Nippur, in Northern Babylonia, where the American expedition has brought to a close its long work of systematic excavation. Here Mr. Haynes has dug down to the very foundations of the great temple of El-lil, and the chief historical results of his labours have been published by Professor Hilprecht (in The Babylonian Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania, vol. i. pl. 2, 1896).

About midway between the summit and the bottom of the mound, Mr. Haynes laid bare a pavement constructed of huge bricks stamped with the names of Sargon of Akkad and his son Naram-Sin. He found also the ancient wall of the city, which had been built by Naram-Sin, 13.7 metres wide. The débris of ruined buildings which lies below the pavement of Sargon is as much as 9.25 metres in depth, while that above it, the topmost stratum of which brings us down to the Christian era, is only 11 metres in height. We may form some idea from this of the enormous age to which the history of Babylonian culture and writing reaches back. In fact, Professor Hilprecht quotes with approval Mr. Haynes's words: "We must cease to apply the adjective 'earliest' to the time of Sargon, or to any age or epoch within a thousand years of his advanced civilization." "The golden age of Babylonian history seems to include the reign of Sargon and of Ur-Gur."

Many of the inscriptions which belong to this remote age of human culture have been published by Professor Hilprecht. Among them is a long inscription, in 132 lines, engraved on multitudes of large stone vases presented to the temple of El-lil by a certain Lugal-zaggisi. Lugal-zaggisi was the son of Ukus, the patesi or high priest of the "Land of the Bow," as Mesopotamia, with its Bedawin inhabitants, was called. He not only conquered Babylonia, then known as Kengi, "the land of canals and reeds," but founded an empire which extended from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. This was centuries before Sargon of Akkad followed in his footsteps. Erech became the capital of Lugal-zaggisi's empire, and doubtless received at this time its Sumerian title of "the city" par excellence.

For a long while previously there had been war between Babylonia and the "Land of the Bow," whose rulers seem to have established themselves in the city of Kis. At one time we find the Babylonian prince En-sag(sag)-ana capturing Kis and its king; at another time it is a king of Kis who makes offerings to the god of Nippur, in gratitude for his victories. To this period belongs the famous "Stela of the Vultures" found at Tello, on which is depicted the victory of E-dingir-ana-gin, the King of Lagas (Tello), over the Semitic hordes of the Land of the Bow. It may be noted that the recent discoveries have shown how correct Professor Maspero has been in assigning the kings of Lagas to a period earlier than that of Sargon of Akkad.

Professor Hilprecht would place E-dingir-ana-gin after Lugal-zaggisi, and see in the Stela of the Vultures a monument of the revenge taken by the Sumerian rulers of Lagas for the conquest of the country by the inhabitants of the north. But it is equally possible that it marks the successful reaction of Chaldsea against the power established by Lugal-zaggisi. However this may be, the dynasty of Lagas (to which Professor Hilprecht has added a new king, En-Khegal) reigned in peace for some time, and belonged to the same age as the first dynasty of Ur. This was founded by a certain Lugal-kigubnidudu, whose inscriptions have been found at Niffer. The dynasty which arose at Ur in later days (cir. b.c. 2700), under Ur-Gur and Bungi, which has hitherto been known as "the first dynasty of Ur," is thus dethroned from its position, and becomes the second. The succeeding dynasty, which also made Ur its capital, and whose kings, Ine-Sin, Pur-Sin IL, and Gimil-Sin, were the immediate predecessors of the first dynasty of Babylon (to which Kharnmurabi belonged), must henceforth be termed the third.

Among the latest acquisitions from Tello are the seals of the patesi, Lugal-usumgal, which finally remove all doubt as to the identity of "Sargani, king of the city," with the famous Sargon of Akkad. The historical accuracy of Sargon's annals, moreover, have been fully vindicated. Not only have the American excavators found the contemporary monuments of him and his son Naram-Sin, but also tablets dated in the years of his campaigns against "the land of the Amorites." In short, Sargon of Akkad, so lately spoken of as "a half-mythical" personage, has now emerged into the full glare of authentic history.

That the native chronologists had sufficient material for reconstructing the past history of their country, is also now clear. The early Babylonian contract-tablets are dated by events which officially distinguished the several years of a king's reign, and tablets have been discovered compiled at the close of a reign which give year by year the events which thus characterised them. One of these tablets, for example, from the excavations at Niffer, begins with the words: (1) "The year when Par-Sin (II.) becomes king. (2) The year when Pur-Sin the king conquers Urbillum," and ends with "the year when Gimil-Sin becomes King of Ur, and conquers the land of Zabsali" in the Lebanon.

Of special interest to the biblical student are the discoveries made by Mr. Pinches among some of the Babylonian tablets which have recently been acquired by the British Museum. Four of them relate to no less a personage than Kudur-Laghghamar or Chedor-laomer, "King of Elam," as well as to Eri-Aku or Arioch, King of Larsa, and his son Dur-makh-ilani; to Tudghula or Tidal, the son of Gazza[ni], and to their war against Babylon in the time of Khamrnu[rabi]. In one of the texts the question is asked, "Who is the son of a king's daughter who has sat on the throne of royalty? Dur-makh-ilani, the son of Eri-Âku, the son of the lady Kur... has sat on the throne of royalty," from which it may perhaps be inferred that Eri-Âku was the son of Kudur-Laghghamar's daughter; and in another we read, "Who is Kudur-Laghghamar, the doer of mischief? He has gathered together the Umman Manda, has devastated the land of Bel (Babylonia), and [has marched] at their side." The Umman Manda were the "Barbarian Hordes" of the Kurdish mountains, on the northern frontier of Elam, and the name corresponds with that of the Goyyim or "nations" in the fourteenth chapter of Genesis. We here see Kudur-Laghghamar acting as their suzerain lord. Unfortunately, all four tablets are in a shockingly broken condition, and it is therefore difficult to discover in them a continuous sense, or to determine their precise nature.

They have, however, been supplemented by further discoveries made by Dr. Scheil at Constantinople. Among the tablets preserved there, he has found letters from Kharnmurabi to his vassal Sin-idinnam of Larsa, from which we learn that Sin-idinnam had been dethroned by the Elamites Kudur-Mabug and Eri-Âku, and had fled for refuge to the court of Kharnmurabi at Babylon. In the war which subsequently broke out between Kharnmurabi and Kudur-Laghghamar, the King of Elam (who, it would seem, exercised suzerainty over Babylonia for seven years), Sin-idinnam gave material assistance to the Babylonian monarch, and Khammurabi accordingly bestowed presents upon him as a "recompense for his valour on the day of the overthrow of Kudur-Laghghamar."

I must also refer to a fine scarab—found in the rubbish-mounds of the ancient city of Kom Ombos, in Upper Egypt—which bears upon it the name of Sutkhu-Apopi. It shows us that the author of the story of the Expulsion of the Hyksôs, in calling the king Ra-Apopi, merely, like an orthodox Egyptian, substituted the name of the god of Heliopolis for that of the foreign deity. Equally interesting are the scarabs brought to light by Professor Flinders Pétrie, on which a hitherto unknown Ya'aqob-hal or Jacob-el receives the titles of a Pharaoh.

In volumes VII., VIII., and IX., Professor Maspero concludes his monumental work on the history of the ancient East. The overthrow of the Persian empire by the Greek soldiers of Alexander marks the beginning of a new era. Europe at last enters upon the stage of history, and becomes the heir of the culture and civilisation of the Orient. The culture which had grown up and developed on the banks of the Euphrates and Nile passes to the West, and there assumes new features and is inspired with a new spirit. The East perishes of age and decrepitude; its strength is outworn, its power to initiate is past. The long ages through which it had toiled to build up the fabric of civilisation are at an end; fresh races are needed to carry on the work which it had achieved. Greece appears upon the scene, and behind Greece looms the colossal figure of the Roman Empire.

During the past decade, excavation has gone on apace in Egypt and Babylonia, and discoveries of a startling and unexpected nature have followed in the wake of excavation. Ages that seemed prehistoric step suddenly forth into the daydawn of history; personages whom a sceptical criticism had consigned to the land of myth or fable are clothed once more with flesh and blood, and events which had been long forgotten demand to be recorded and described. In Babylonia, for example, the excavations at Niffer and Tello have shown that Sargon of Akkad, so far from being a creature of romance, was as much a historical monarch as Nebuchadrezzar himself; monuments of his reign have been discovered, and we learn from them that the empire he is said to have founded had a very real existence. Contracts have been found dated in the years when he was occupied in conquering Syria and Palestine, and a cadastral survey that was made for the purposes of taxation mentions a Canaanite who had been appointed "governor of the land of the Amorites." Even a postal service had already been established along the high-roads which knit the several parts of the empire together, and some of the clay seals which franked the letters are now in the Museum of the Louvre.

At Susa, M. de Morgan, the late director of the Service of Antiquities in Egypt, has been excavating below the remains of the Achremenian period, among the ruins of the ancient Elamite capital. Here he has found numberless historical inscriptions, besides a text in hieroglyphics which may cast light on the origin of the cuneiform characters. But the most interesting of his discoveries are two Babylonian monuments that were carried off by Elamite conquerors from the cities of Babylonia. One of them is a long inscription of about 1200 lines belonging to Manistusu, one of the early Babylonian kings, whose name has been met with at Niffer; the other is a monument of Naram-Sin, the Son of Sargon of Akkad, which it seems was brought as booty to Susa by Simti-silkhak, the grandfather, perhaps, of Eriaku or Arioch.

In Armenia, also, equally important inscriptions have been found by Belck and Lehmann. More than two hundred new ones have been added to the list of Vannic texts. It has been discovered from them that the kingdom of Biainas or Van was founded by Ispuinis and Menuas, who rebuilt Yan itself and the other cities which they had previously sacked and destroyed. The older name of the country was Kumussu, and it may be that the language spoken in it was allied to that of the Hittites, since a tablet in hieroglyphics of the Hittite type has been unearthed at Toprak Kaleh. One of the newly-found inscriptions of Sarduris III. shows that the name of the Assyrian god, hitherto read Ramman or Rimmon, was really pronounced Hadad. It describes a war of the Vannic king against Assur-nirari, son of Hadad-nirari (A-da-di-ni-ra-ri) of Assyria, thus revealing not only the true form of the Assyrian name, but also the parentage of the last king of the older Assyrian dynasty. From another inscription, belonging to Rusas II., the son of Argistis, we learn that campaigns were carried on against the Hittites and the Moschi in the latter years of Sennacherib's reign, and therefore only just before the irruption of the Kimmerians into the northern regions of Western Asia.

The two German explorers have also discovered the site and even the ruins of Muzazir, called Ardinis by the people of Van. They lie on the hill of Shkenna, near Topsanâ, on the road between Kelishin and Sidek. In the immediate neighbourhood the travellers succeeded in deciphering a monument of Rusas I., partly in Vannic, partly in Assyrian, from which it appears that the Vannic king did not, after all, commit suicide when the news of the fall of Muzazir was brought to him, as is stated by Sargon, but that, on the contrary, he "marched against the mountains of Assyria" and restored the fallen city itself. Urzana, the King of Muzazir, had fled to him for shelter, and after the departure of the Assyrian army he was sent back by Rusas to his ancestral domains. The whole of the district in which Muzazir was situated was termed Lulu, and was regarded as the southern province of Ararat. In it was Mount Nizir, on whose summit the ark of the Chaldsean Noah rested, and which is therefore rightly described in the Book of Genesis as one of "the mountains of Ararat." It was probably the Rowandiz of to-day.

The discoveries made by Drs. Belck and Lehmann, however, have not been confined to Vannic texts. At the sources of the Tigris Dr. Lehmann has found two Assyrian inscriptions of the Assyrian king, Shalmaneser IL, one dated in his fifteenth and the other in his thirty-first year, and relating to his campaigns against Aram of Ararat. He has further found that the two inscriptions previously known to exist at the same spot, and believed to belong to Tiglath-Ninip and Assur-nazir-pal, are really those of Shalmaneser II., and refer to the war of his seventh year.

But it is from Egypt that the most revolutionary revelations have come. At Abydos and Kom el-Ahmar, opposite El-Kab, monuments have been disinterred of the kings of the first and second dynasties, if not of even earlier princes; while at Negada, north of Thebes, M. de Morgan has found a tomb which seems to have been that of Menés himself. A new world of art has been opened out before us; even the hieroglyphic system of writing is as yet immature and strange. But the art is already advanced in many respects; hard stone was cut into vases and bowls, and even into statuary of considerable artistic excellence; glazed porcelain was already made, and bronze, or rather copper, was fashioned into weapons and tools. The writing material, as in Babylonia, was often clay, over which seal-cylinders of a Babylonian pattern were rolled. Equally Babylonian are the strange and composite animals engraved on some of the objects of this early age, as well as the structure of the tombs, which were built, not of stone, but of crude brick, with their external walls panelled and pilastered. Professor Hommel's theory, which brings Egyptian civilisation from Babylonia along with the ancestors of the historical Egyptians, has thus been largely verified.

But the historical Egyptians were not the first inhabitants of the valley of the Nile. Not only have palaeolithic implements been found on the plateau of the desert; the relics of neolithic man have turned up in extraordinary abundance. When the historical Egyptians arrived with their copper weapons and their system of writing, the land was already occupied by a pastoral people, who had attained a high level of neolithic culture. Their implements of flint are the most beautiful and delicately finished that have ever been discovered; they were able to carve vases of great artistic excellence out of the hardest of stone, and their pottery was of no mean quality. Long after the country had come into the possession of the historical dynasties, and had even been united into a single monarchy, their settlements continued to exist on the outskirts of the desert, and the neolithic culture that distinguished them passed only gradually away. By degrees, however, they intermingled with their conquerors from Asia, and thus formed the Egyptian race of a later day. But they had already made Egypt what it has been throughout the historical period. Under the direction of the Asiatic immigrants and of the eugineering science whose first home had been in the alluvial plain of Babylonia, they accomplished those great works of irrigation which confined the Nile to its present channel, which cleared away the jungle and the swamp that had formerly bordered the desert, and turned them into fertile fields. Theirs were the hands which carried out the plans of their more intelligent masters, and cultivated the valley when once it had been reclaimed. The Egypt of history was the creation of a twofold race: the Egyptians of the monuments supplied the controlling and directing power; the Egyptians of the neolithic graves bestowed upon it their labour and their skill.

The period treated of by Professor Maspero in these volumes is one for which there is an abundance of materials sucli as do not exist for the earlier portions of his history. The evidence of the monuments is supplemented by that of the Hebrew and classical writers. But on this very account it is in some respects more difficult to deal with, and the conclusions arrived at by the historian are more open to question and dispute. In some cases conflicting accounts are given of an event which seem to rest on equally good authority; in other cases, there is a sudden failure of materials just where the thread of the story becomes most complicated. Of this the decline and fall of the Assyrian empire is a prominent example; for our knowledge of it, we have still to depend chiefly on the untrustworthy legends of the Greeks. Our views must be coloured more or less by our estimate of Herodotos; those who, like myself, place little or no confidence in what he tells us about Oriental affairs will naturally form a very different idea of the death-struggle, of Assyria from that formed by writers who still see in him the Father of Oriental History.

Even where the native monuments have come to our aid, they have not unfrequently introduced difficulties and doubts where none seemed to exist before, and have made the task of the critical historian harder than ever. Cyrus and his forefathers, for instance, turn out to have been kings of Anzan, and not of Persia, thus explaining why it is that the Neo-Susian language appears by the side of the Persian and the Babylonian as one of the three official languages of the Persian empire; but we still have to learn what was the relation of Anzan to Persia on the one hand, and to Susa on the other, and when it was that Cyrus of Anzan became also King of Persia. In the Annalistic Tablet, he is called "King of Persia" for the first time in the ninth year of Nabonidos.

Similar questions arise as to the position and nationality of Astyages. He is called in the inscriptions, not a Mede, but a Manda—a name which, as I showed many years ago, meant for the Babylonian a "barbarian" of Kurdistan. I have myself little doubt that the Manda over whom Astyages ruled were the Scythians of classical tradition, who, as may be gathered from a text published by Mr. Strong, had occupied the ancient kingdom of Ellipi. It is even possible that in the Madyes of Herodotos, we have a reminiscence of the Manda of the cuneiform inscriptions. That the Greek writers should have confounded the Madâ or Medes with the Manda or Barbarians is not surprising; we find even Berossos describing one of the early dynasties of Babylonia as "Median" where Manda, and not Madâ, must plainly be meant.

These and similar problems, however, will doubtless be cleared up by the progress of excavation and research. Perhaps M. de Morgan's excavations at Susa may throw some light on them, but it is to the work of the German expedition, which has recently begun the systematic exploration of the site of Babylon, that we must chiefly look for help. The Babylon of Nabopolassar and Nebuchadrezzar rose on the ruins of Nineveh, and the story of downfall of the Assyrian empire must still be lying buried under its mounds.

In completing the translation of this great work, I have to thank Professor Maspero for kindly permitting me to appeal to him on various questions which arose while preparing the translation. His patience and courtesy have alike been unfailing in every matter submitted for his decision.

I am indebted to Miss Bradbury for kindly supplying, in the midst of much other literary work for the Egypt Exploration Fund, the translation of the chapter on the gods, and also of the earlier parts of some of the first chapters. She has, moreover, helped me in my own share of the work with many suggestions and hints, which her intimate connection with the late Miss Amelia B. Edwards fully qualified her to give.

As in the original there is a lack of uniformity in the transcription and accentuation of Arabic names, I have ventured to alter them in several cases to the form most familiar to English readers.

The spelling of the ancient Egyptian words has, at Professor Maspero's request, been retained throughout, with the exception that the French ou has been invariably represented by û, e.g. Khnoumou by Khnûmû.

By an act of international courtesy, the director of the Imprimerie Nationale has allowed the beautifully cut hieroglyphic and cuneiform type used in the original to be employed in the English edition, and I take advantage of this opportunity to express to him our thanks and appreciation of his graceful act.

M. L. McClure.

THE RIVER AND ITS INFLUENCE UPON THE FORMATION AND CHARACTER OF THE COUNTRY—THE OLDEST INHABITANTS OF THE LAND—THE FIRST POLITICAL ORGANIZATION OF THE VALLEY.

The Delta: its gradual formation, its structure, its canals—The valley of Egypt—The two arms of the river—The Eastern Nile—The appearance of its hanks—The hills—The gorge of Gehel Silsileh—The cataracts: the falls of Aswan—Nubia—The rapids of Wady Halfah—The Takazze—The Blue Nile and the White Nile.

The sources of the Nile—The Egyptian cosmography—The four pillars and the four upholding mountains—The celestial Nile the source of the terrestial Nile—the Southern Sea and the islands of Spirits—The tears of Isis—The rise of the Nile—The Green Nile and the Bed Nile—The opening of the dykes—-The fall of the Nile—The river at its lowest ebb.

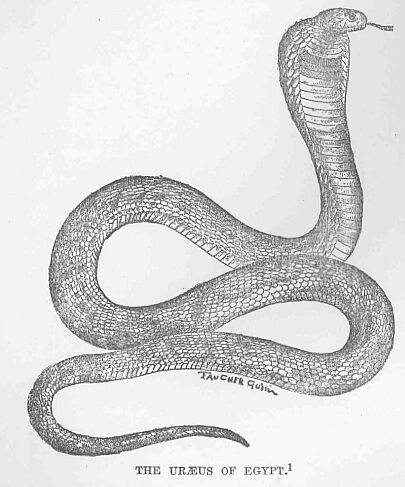

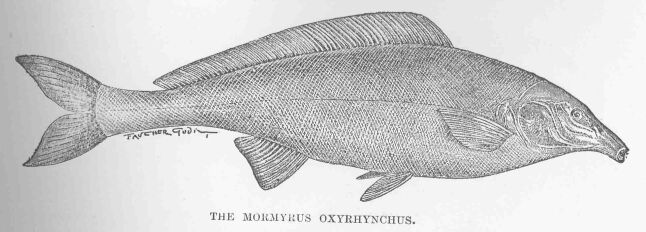

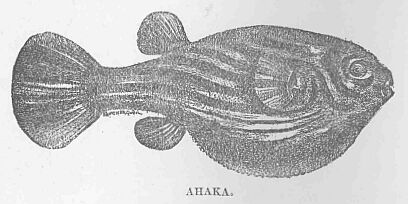

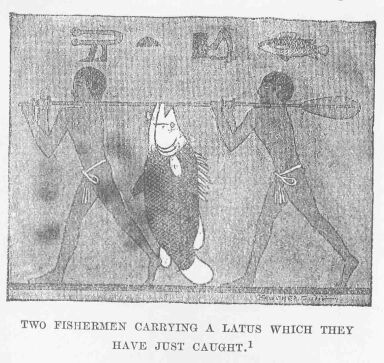

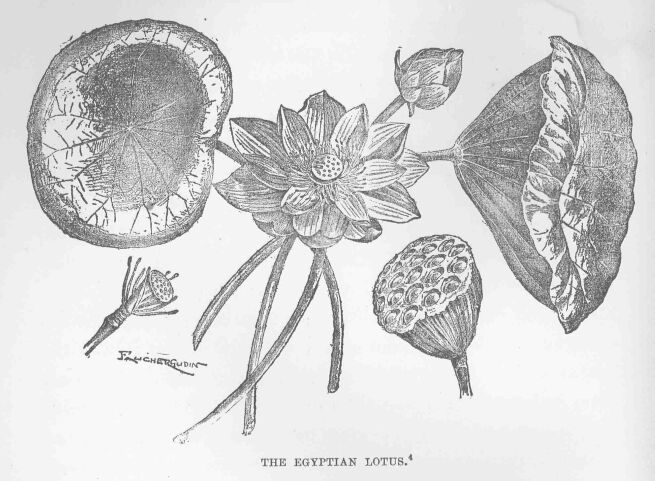

The alluvial deposits and the effects of the inundation upon the soil of Egypt—Paucity of the flora: aquatic plants, the papyrus and the lotus; the sycamore and the date-palm, the acacias, the dôm-palms—The fauna: the domestic and wild animals; serpents, the urstus; the hippopotamus and the crocodile; birds; fish, the fahaka.

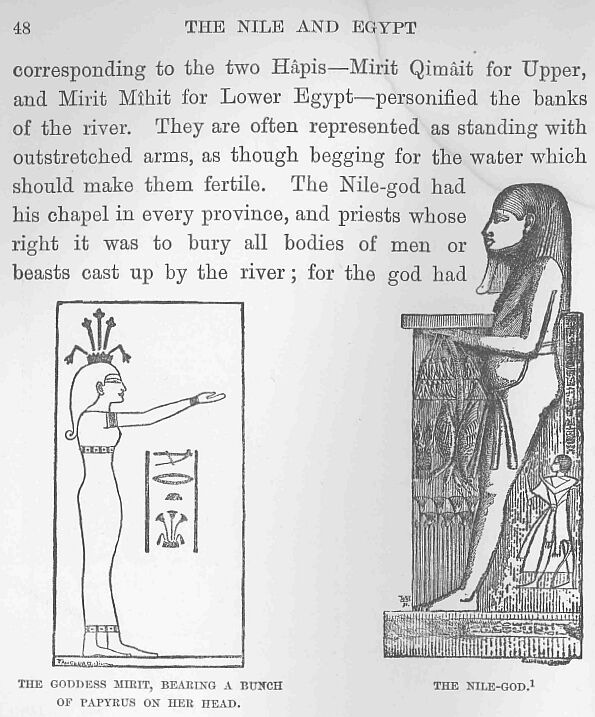

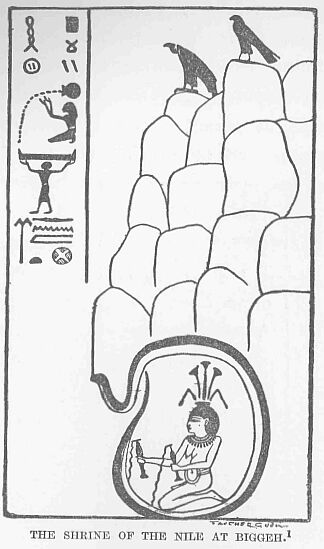

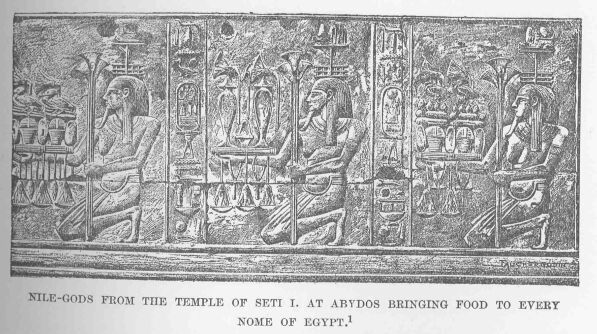

The Nile god: his form and its varieties—The goddess Mirit—The supposed sources of the Nile at Elephantine—The festivals of Gebel Silsileh-Hymn to the Nile from papyri m the British Museum.

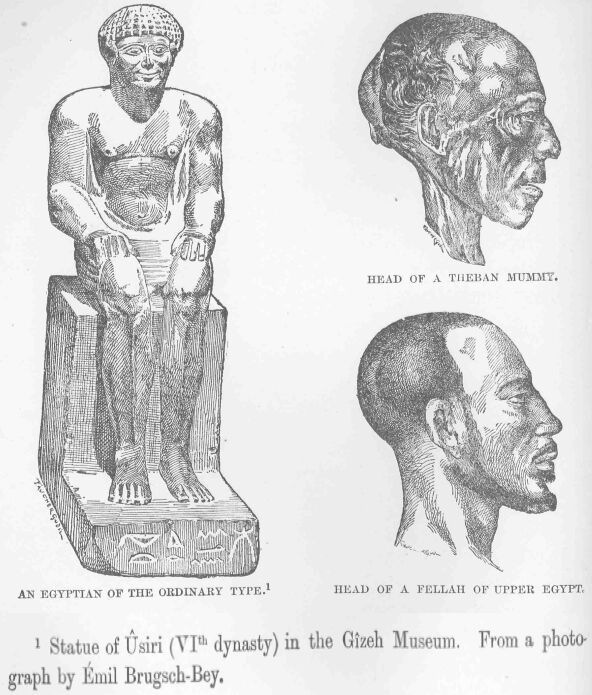

The names of the Nile and Egypt: Bomitu and Qimit—Antiquity of the Egyptianpeople—Their first horizon—The hypothesis of their Asiatic origin—The probability of their African origin—The language and its Semitic affinities—The race and its principal types.

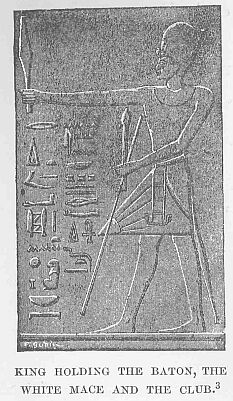

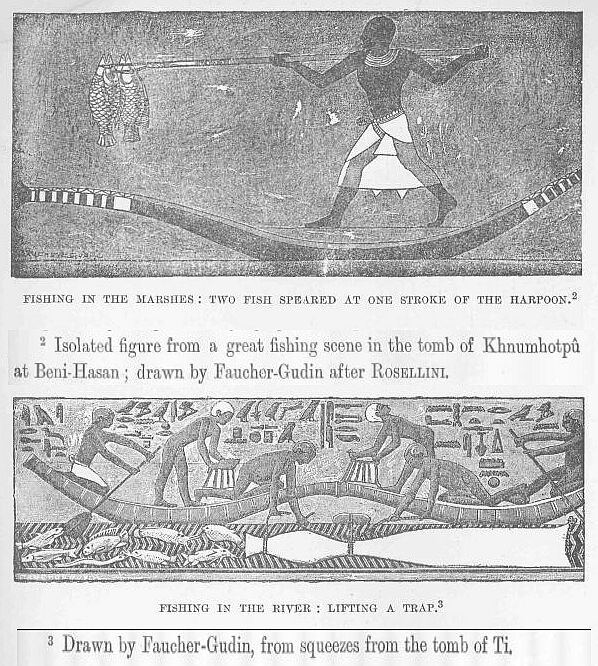

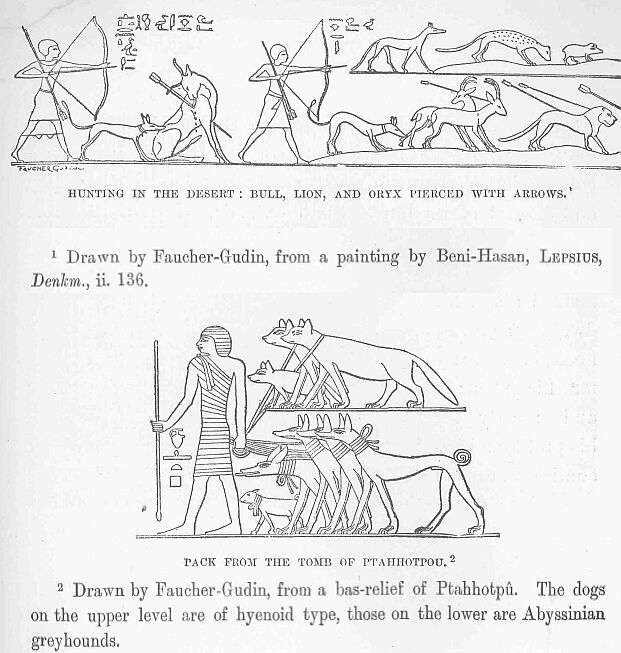

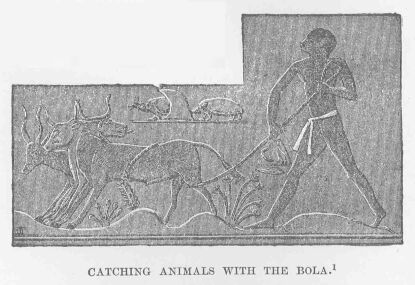

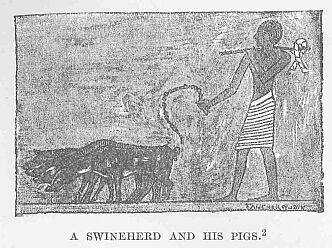

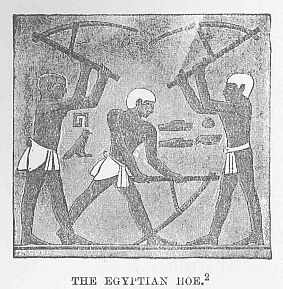

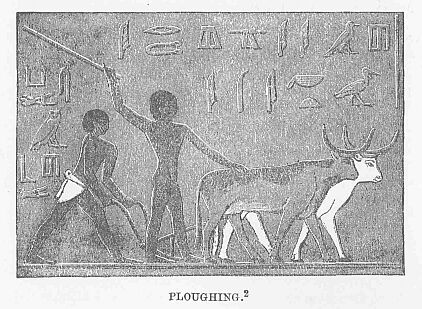

The primitive civilization of Egypt—Its survival into historic times—The women of Amon—Marriage—Rights of women and children—Houses—Furniture—Dress—Jewels—Wooden and metal arms—Primitive life-Fishing and hunting—The lasso and "bolas"—The domestication of animals—Plants used for food—The lotus—Cereals—The hoe and the plough.

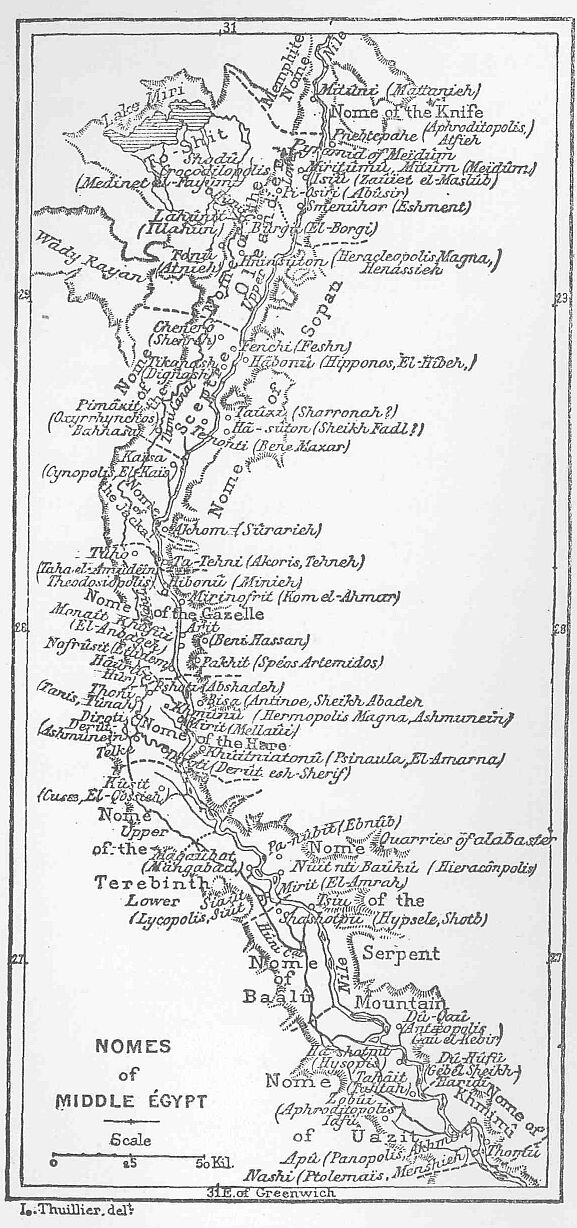

The conquest of the valley—Dykes—Basins—Irrigation—The princes—The nomes—The first local principalities—Late organization of the Delta—Character of its inhabitants—Gradual division of the principalities and changes of then areas—The god of the city.

The river and its influence upon the formation of the country—The oldest inhabitants of the valley and its first political organization.

* The same expression has been attributed to Hecatseus of

Miletus. It has often been observed that this phrase seems

Egyptian on the face of it, and it certainly recalls such

forms of expression as the following, taken from a formula

frequently found on funerary "All things created by heaven,

given by earth, brought by the Nile—from its mysterious

sources." Nevertheless, up to the present time, the

hieroglyphic texts have yielded nothing altogether

corresponding to the exact terms of the Greek historians—

gift of the Nile, or its natural product.

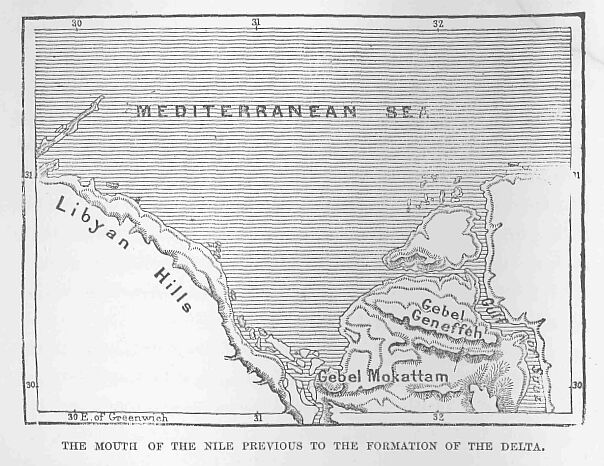

A long low, level shore, scarcely rising above the sea, a chain of vaguely defined and ever-shifting lakes and marshes, then the triangular plain beyond, whose apex is thrust thirty leagues into the land—this, the Delta of Egypt, has gradually been acquired from the sea, and is as it were the gift of the Nile. The Mediterranean once reached to the foot of the sandy plateau on which stand the Pyramids, and formed a wide gulf where now stretches plain beyond plain of the Delta. The last undulations of the Arabian hills, from Gebel Mokattam to Gebel Geneffeh, were its boundaries on the east, while a sinuous and shallow channel running between Africa and Asia united the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. Westward, the littoral followed closely the contour of the Libyan plateau; but a long limestone spur broke away from it at about 31° N., and terminated in Cape Abûkîr. The alluvial deposits first tilled up the depths of the bay, and then, under the influence of the currents which swept along its eastern coasts, accumulated behind that rampart of sand-hills whose remains are still to be seen near Benha. Thus was formed a miniature Delta, whose structure pretty accurately corresponded with that of the great Delta of to-day. Here the Nile divided into three divergent streams, roughly coinciding with the southern courses of the Rosetta and Damietta branches, and with the modern canal of Abu Meneggeh. The ceaseless accumulation of mud brought down by the river soon overpassed the first limits, and steadily encroached upon the sea until it was carried beyond the shelter furnished by Cape Abûkîr. Thence it was gathered into the great littoral current flowing from Africa to Asia, and formed an incurvated coast-line ending in the headland of Casios, on the Syrian frontier. From that time Egypt made no further increase towards the north, and her coast remains practically such as it was thousands of years ago:[*] the interior alone has suffered change, having been dried up, hardened, and gradually raised. Its inhabitants thought they could measure the exact length of time in which this work of creation had been accomplished. According to the Egyptians, Menés, the first of their mortal kings, had found, so they said, the valley under water. The sea came in almost as far as the Fayûm, and, excepting the province of Thebes, the whole country was a pestilential swamp. Hence, the necessary period for the physical formation of Egypt would cover some centuries after Menés. This is no longer considered a sufficient length of time, and some modern geologists declare that the Nile must have worked at the formation of its own estuary for at least seventy-four thousand years.[**]

* Élie de Beaumont, "The great distinction of the Nile Delta

lies in the almost uniform persistence of its coast-line....

The present sea-coast of Egypt is little altered from that

of three thousand years ago." The latest observations

prove it to be sinking and shrinking near Alexandria to rise

in the neighbourhood of Port Said.

** Others, as for example Schweinfurth, are more moderate

in their views, and think "that it must have taken about

twenty thousand years for that alluvial deposit which now

forms the arable soil of Egypt to have attained to its

present depth and fertility."

This figure is certainly exaggerated, for the alluvium would gain on the shallows of the ancient gulf far more rapidly than it gains upon the depths of the Mediterranean. But even though we reduce the period, we must still admit that the Egyptians little suspected the true age of their country. Not only did the Delta long precede the coming of Menés, but its plan was entirely completed before the first arrival of the Egyptians. The Greeks, full of the mysterious virtues which they attributed to numbers, discovered that there were seven principal branches, and seven mouths of the Nile, and that, as compared with these, the rest were but false mouths.

As a matter of fact, there were only three chief outlets. The Canopic branch flowed westward, and fell into the Mediterranean near Cape Abûkîr, at the western extremity of the arc described by the coast-line. The Pelusiac branch followed the length of the Arabian chain, and flowed forth at the other extremity; and the Sebennytic stream almost bisected the triangle contained between the Canopic and Pelusiac channels. Two thousand years ago, these branches separated from the main river at the city of Cerkasoros, nearly four miles north of the site where Cairo now stands. But after the Pelusiac branch had ceased to exist, the fork of the river gradually wore away the land from age to age, and is now some nine miles lower down.[*] These three great waterways are united by a network of artificial rivers and canals, and by ditches—some natural, others dug by the hand of man, but all ceaselessly shifting. They silt up, close, open again, replace each other, and ramify in innumerable branches over the surface of the soil, spreading life and fertility on all sides. As the land rises towards the south, this web contracts and is less confused, while black mould and cultivation alike dwindle, and the fawn-coloured line of the desert comes into sight. The Libyan and Arabian hills appear above the plain, draw nearer to each other, and gradually shut in the horizon until it seems as though they would unite. And there the Delta ends, and Egypt proper has begun.

It is only a strip of vegetable mould stretching north and south between regions of drought and desolation, a prolonged oasis on the banks of the river, made by the Nile, and sustained by the Nile. The whole length of the land is shut in between two ranges of hills, roughly parallel at a mean distance of about twelve miles.[**]

* By the end of the Byzantine period, the fork of the river

lay at some distance south of Shetnûfi, the present

Shatanûf, which is the spot where it now is. The Arab

geographers call the head of the Delta Batn-el-Bagaraji, the

Cow's Belly. Ampère, in his Voyage en Egypte et en Nubie, p.

120, says,—"May it not be that this name, denoting the place

where the most fertile part of Egypt begins, is a

reminiscence of the Cow Goddess, of Isis, the symbol of

fecundity, and the personification of Egypt?"

**De Rozière estimated the mean breadth as being only a

little over nine miles.

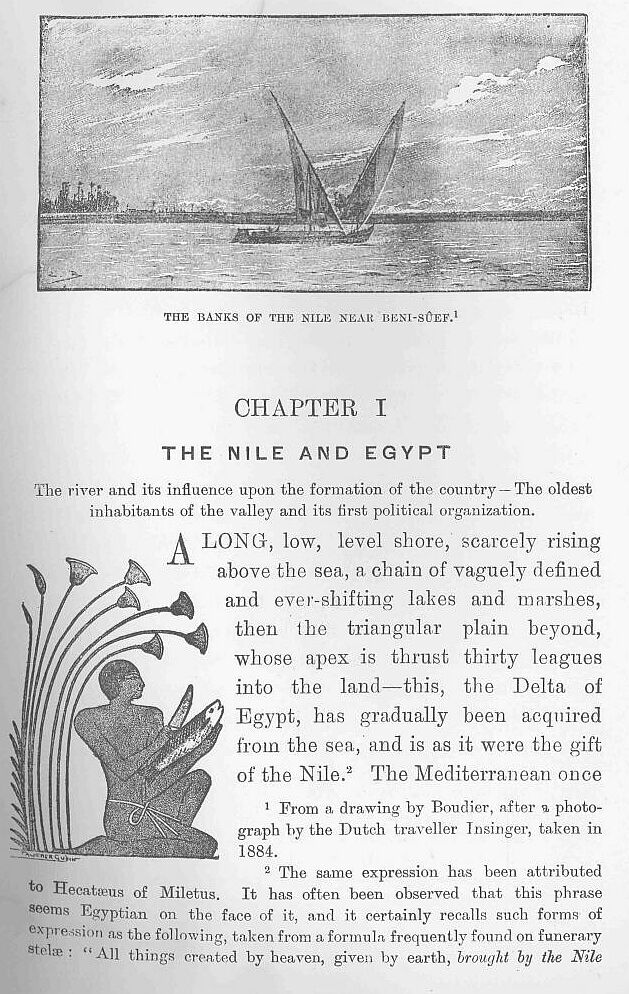

During the earlier ages, the river filled all this intermediate space, and the sides of the hills, polished, worn, blackened to their very summits, still bear unmistakable traces of its action. Wasted, and shrunken within the deeps of its ancient bed, the stream now makes a way through its own thick deposits of mud. The bulk of its waters keeps to the east, and constitutes the true Nile, the "Great River" of the hieroglyphic inscriptions. A second arm flows close to the Libyan desert, here and there formed into canals, elsewhere left to follow its own course. From the head of the Delta to the village of Demt it is called the Bahr-Yûsuf; beyond Derût—up to Gebel Silsileh—it is the Ibrâhimîyeh, the Sohâgîyeh, the Raiân. But the ancient names are unknown to us. This Western Nile dries up in winter throughout all its upper courses: where it continues to flow, it is by scanty accessions from the main Nile. It also divides north of Henassieh, and by the gorge of Illahûn sends out a branch which passes beyond the hills into the basin of the Fayûrn. The true Nile, the Eastern Nile, is less a river than a sinuous lake encumbered with islets and sandbanks, and its navigable channel winds capriciously between them, flowing with a strong and steady current below the steep, black banks cut sheer through the alluvial earth.

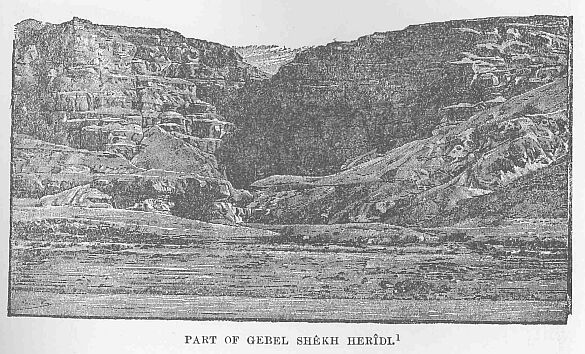

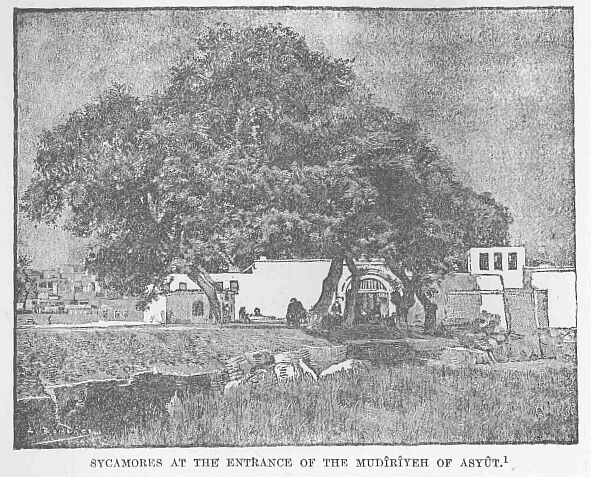

1 From a drawing by Boudier, after a photograph by

Insinger, taken in 1884.

There are light groves of the date-palm, groups of acacia trees and sycamores, square patches of barley or of wheat, fields of beans or of bersîm,[*] and here and there a long bank of sand which the least breeze raises into whirling clouds. And over all there broods a great silence, scarcely broken by the cry of birds, or the song of rowers in a passing boat.

* Bersîm is a kind of trefoil, the Trifolium Alexandrinum

of LINNÆUS. It is very common in Egypt, and the only plant

of the kind generally cultivated for fodder.

Something of human life may stir on the banks, but it is softened into poetry by distance. A half-veiled woman, bearing a bundle of herbs upon her head, is driving her goats before her. An irregular line of asses or of laden camels emerges from one hollow of the undulating road only to disappear within another. A group of peasants, crouched upon the shore, in the ancient posture of knees to chin, patiently awaits the return of the ferry-boat.

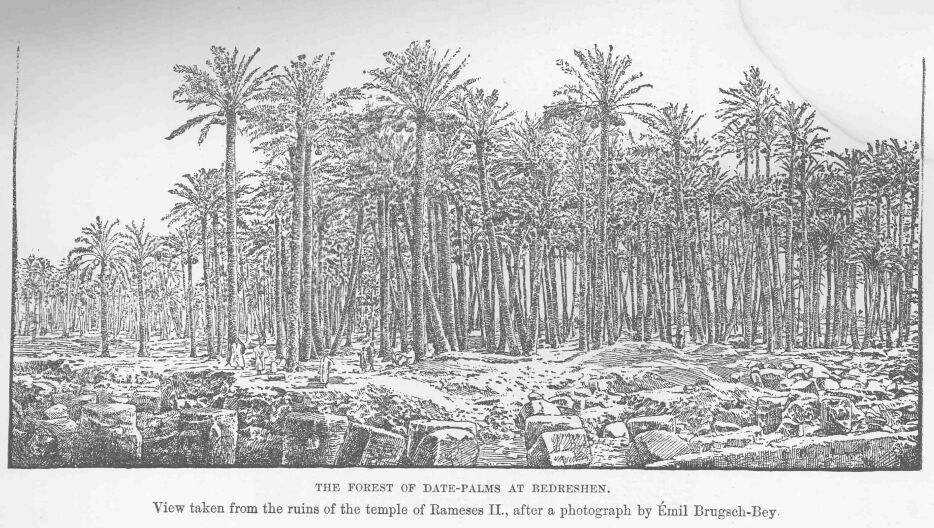

1 From a drawing by Boudier, after a photograph by

Insinger, taken in 1886.

A dainty village looks forth smiling from beneath its palm trees. Near at hand it is all naked filth and ugliness: a cluster of low grey huts built of mud and laths; two or three taller houses, whitewashed; an enclosed square shaded by sycamores; a few old men, each seated peacefully at his own door; a confusion of fowls, children, goats, and sheep; half a dozen boats made fast ashore. But, as we pass on, the wretchedness all fades away; meanness of detail is lost in light, and long before it disappears at a bend of the river, the village is again clothed with gaiety and serene beauty. Day by day, the landscape repeats itself. The same groups of trees alternate with the same fields, growing green or dusty in the sunlight according to the season of the year. With the same measured flow, the Nile winds beneath its steep banks and about its scattered islands.

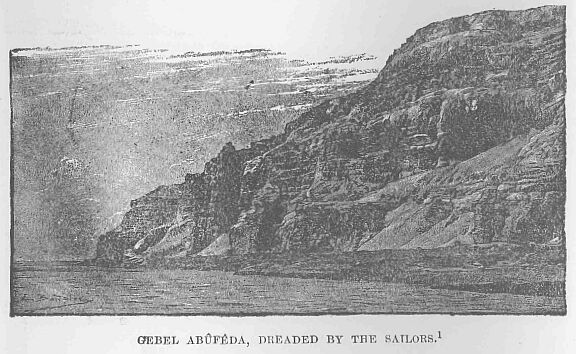

1 From a drawing by Boudier, after a photograph by Insinger,

taken in 1882.

One village succeeds another, each alike smiling and sordid under its crown of foliage. The terraces of the Libyan hills, away beyond the Western Nile, scarcely rise above the horizon, and lie like a white edging between the green of the plain and the blue of the sky. The Arabian hills do not form one unbroken line, but a series of mountain masses with their spurs, now approaching the river, and now withdrawing to the desert at almost regular intervals. At the entrance to the valley, rise Gebel Mokattam and Gebel el-Ahmar. Gebel Hemûr-Shemûl and Gebel Shêkh Embârak next stretch in echelon from north to south, and are succeeded by Gebel et-Ter, where, according to an old legend, all the birds of the world are annually assembled.[*]

* In Makrizi's Description of Egypt we read: "Every year,

upon a certain day, all the herons (Boukîr, Ardea bubulcus

of Cuvier) assemble at this mountain. One after another,

each puts his beak into a cleft of the hill until the cleft

closes upon one of them. And then forthwith all the others

fly away But the bird which has been caught struggles until

he dies, and there his body remains until it has fallen into

dust." The same tale is told by other Arab writers, of which

a list may be seen in Etienne Quatremère, Mémoires

historiques et géographiques sur l'Egypte et quelques

contrées voisines, vol. i. pp. 31-33. It faintly recalls

that ancient tradition of the Cleft at Abydos, whereby souls

must pass, as human-headed birds, in order to reach the

other world.

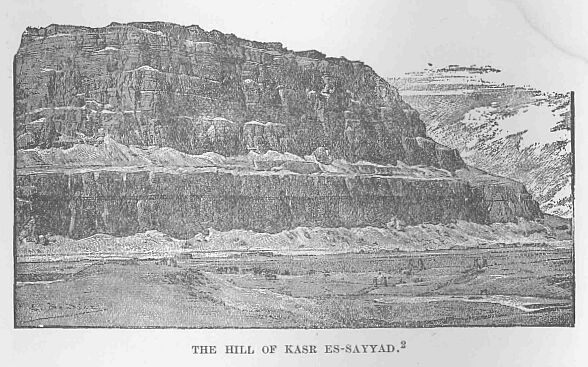

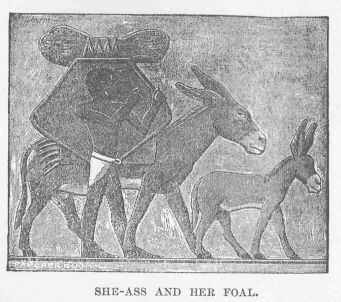

2 From a drawing by Boudier, after a photograph by

insinger, taken in 1882.

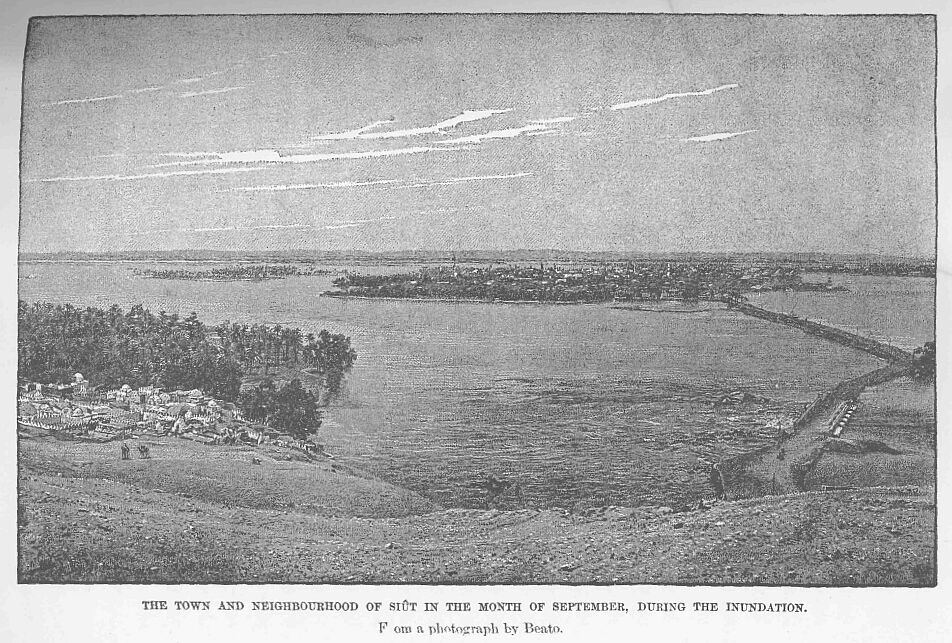

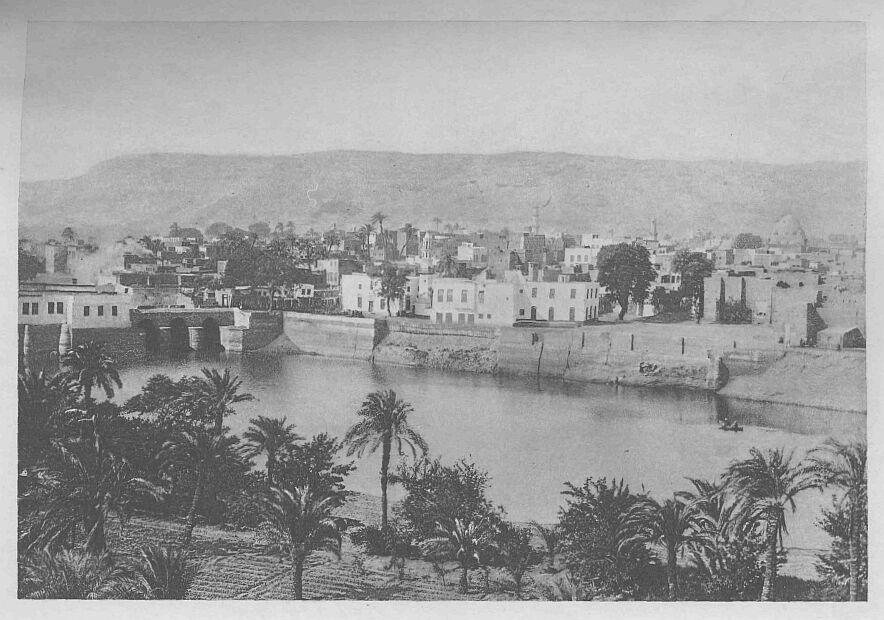

Then follows Gebel Abûfêda, dreaded by the sailors for its sudden gusts. Limestone predominates throughout, white or yellowish, broken by veins of alabaster, or of red and grey sandstones. Its horizontal strata are so symmetrically laid one above another as to seem more like the walls of a town than the side of a mountain. But time has often dismantled their summits and loosened their foundations. Man has broken into their façades to cut his quarries and his tombs; while the current is secretly undermining the base, wherein it has made many a breach. As soon as any margin of mud has collected between cliffs and river, halfah and wild plants take hold upon it, and date-palms grow there—whence their seed, no one knows. Presently a hamlet rises at the mouth of the ravine, among clusters of trees and fields in miniature. Beyond Siût, the light becomes more glowing, the air drier and more vibrating, and the green of cultivation loses its brightness. The angular outline of the dom-palni mingles more and more with that of the common palm and of the heavy sycamore, and the castor-oil plant increasingly abounds. But all these changes come about so gradually that they are effected before we notice them. The plain continues to contract. At Thebes it is still ten miles wide; at the gorge of Gebelên it has almost disappeared, and at Gebel Silsileh it has completely vanished. There, it was crossed by a natural dyke of sandstone, through which the waters have with difficulty scooped for themselves a passage. From this point, Egypt is nothing but the bed of the Nile lying between two escarpments of naked rock.

Further on the cultivable land reappears, but narrowed, and changed almost beyond recognition. Hills, hewn out of solid sandstone, succeed each other at distances of about two miles, low, crushed, sombre, and formless. Presently a forest of palm trees, the last on that side, announces Aswan and Nubia. Five banks of granite, ranged in lines between latitude 24° and 18° N., cross Nubia from east to west, and from north-east to south-west, like so many ramparts thrown up between the Mediterranean and the heart of Africa. The Nile has attacked them from behind, and made its way over them one after another in rapids which have been glorified by the name of cataracts.

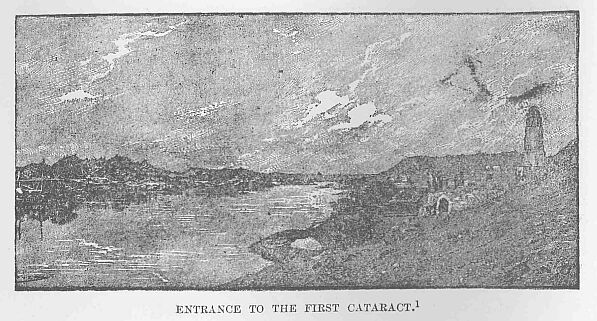

1 View taken from the hills opposite Elephantine, by

Insinger, in 1884.

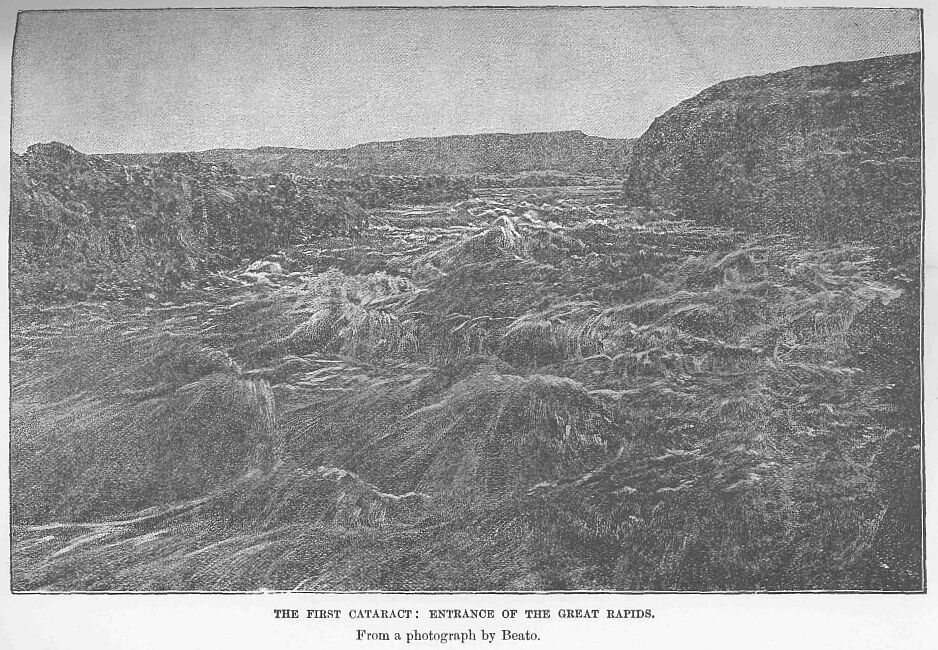

Classic writers were pleased to describe the river as hurled into the gulfs of Syne with so great a roar that the people of the neighbourhood were deafened by it. Even a colony of Persians, sent thither by Cambyses, could not bear the noise of the falls, and went forth to seek a quieter situation. The first cataract is a kind of sloping and sinuous passage six and a quarter miles in length, descending from the island of Philae to the port of Aswan, the aspect of its approach relieved and brightened by the ever green groves of Elephantine. Beyond Elephantine are cliffs and sandy beaches, chains of blackened "roches moutonnées" marking out the beds of the currents, and fantastic reefs, sometimes bare and sometimes veiled by long grasses and climbing plants, in which thousands of birds have made their nests. There are islets too, occasionally large enough to have once supported something of a population, such as Amerade, Salûg, Sehêl. The granite threshold of Nubia, is broken beyond Sehêl, but its débris, massed m disorder against the right bank, still seem to dispute the passage of the waters, dashing turbulently and roaring as they flow along through tortuous channels, where every streamlet is broken up into small cascades, ihe channel running by the left bank is always navigable.

During the inundation, the rocks and sandbanks of the right side are completely under water, and their presence is only betrayed by eddies. But on the river's reaching its lowest point a fall of some six feet is established, and there big boats, hugging the shore, are hauled up by means of ropes, or easily drift down with the current.

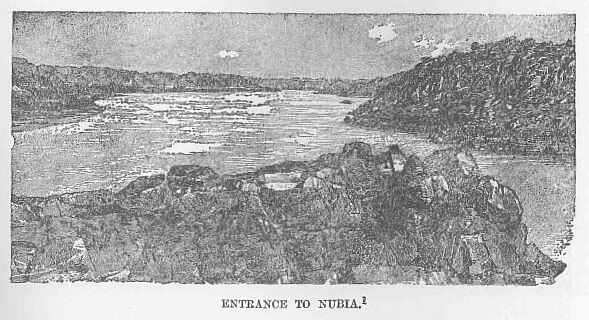

1 From a drawing by Boudier, after a photograph by Insinger,

taken in 1881.

All kinds of granite are found together in this corner of Africa. There are the pink and red Syenites, porphyritic granite, yellow granite, grey granite, both black granite and white, and granites veined with black and veined with white. As soon as these disappear behind us, various sandstones begin to crop up, allied to the coarsest calcaire grossier. The hill bristle with small split blocks, with peaks half overturned, with rough and denuded mounds. League beyond league, they stretch in low ignoble outline. Here and there a valley opens sharply into the desert, revealing an infinite perspective of summits and escarpments in echelon one behind another to the furthest plane of the horizon, like motionless caravans. The now confined river rushes on with a low, deep murmur, accompanied night and day by the croaking of frogs and the rhythmic creak of the sâkîeh.[*]

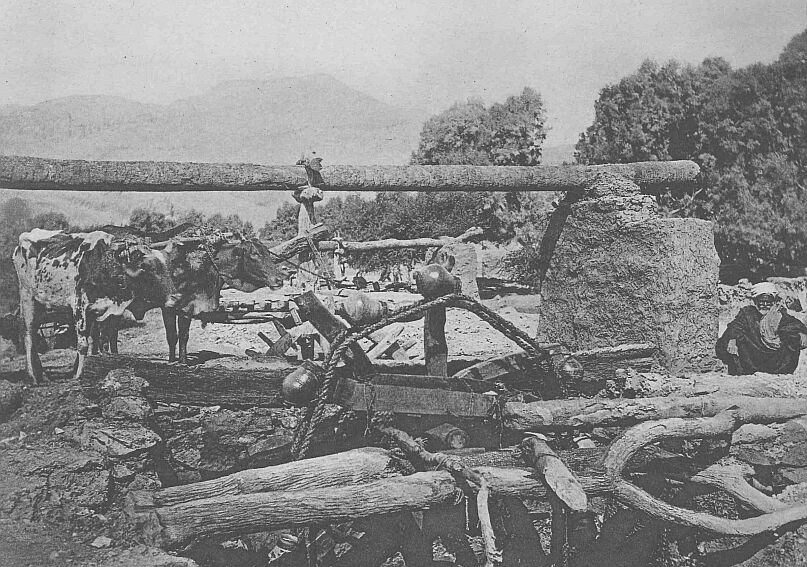

* The sâkîeh is made of a notch-wheel fixed vertically on a

horizontal axle, and is actuated by various cog-wheels set

in continuous motion by oxen or asses. A long chain of

earthenware vessels brings up the water either from the

river itself, or from some little branch canal, and

empties it into a system of troughs and reservoirs.

Thence, it flows forth to be distributed over all the

neighbouring land.

Jetties of rough stone-work, made in unknown times by an unknown people, run out like breakwaters into midstream.

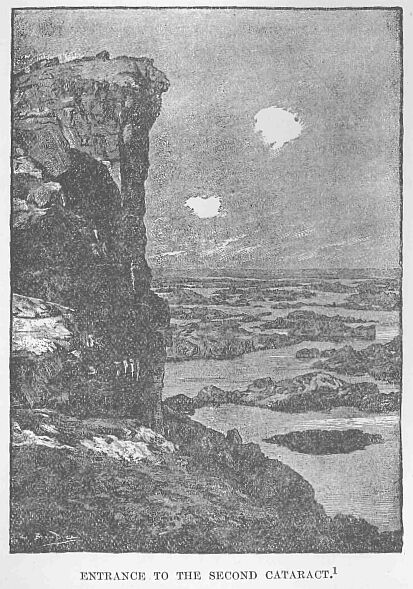

From time to time waves of sand are borne over, and drown the narrow fields of durra and of barley. Scraps of close, aromatic pasturage, acacias, date-palms, and dôm-palms, together with a few shrivelled sycamores, are scattered along both banks. The ruins of a crumbling pylon mark the site of some ancient city, and, overhanging the water, is a vertical wall of rock honeycombed with tombs. Amid these relics of another age, miserable huts, scattered hamlets, a town or two surrounded with little gardens are the only evidence that there is yet life in Nubia. South of Wâdy Halfah, the second granite bank is broken through, and the second cataract spreads its rapids over a length of four leagues: the archipelago numbers more than 350 islets, of which some sixty have houses upon them and yield harvests to their inhabitants. The main characteristics of the first two cataracts are repeated with slight variations in the cases of the three which follow,—at Hannek, at Guerendid, and El-Hu-mar. It is Egypt still, but a joyless Egypt bereft of its brightness: impoverished, disfigured, and almost desolate.

1 View taken from the top of the rocks of Abusîr, after a

photograph by Insinger, in 1881.

There is the same double wall of hills, now closely confining the valley, and again withdrawing from each other as though to flee into the desert. Everywhere are moving sheets of sand, steep black banks with their narrow strips of cultivation, villages which are scarcely visible on account of the lowness of their huts sycamore ceases at Gebel-Barkal, date-palms become fewer and finally disappear. The Nile alone has not changed. And it was at Philse, so it is at Berber. Here, however, on the right bank, 600 leagues from the sea, is its first affluent, the Takazze, which intermittently brings to it the waters of Northern Ethiopia. At Khartum, the single channel in which the river flowed divides; and two other streams are opened up in a southerly direction, each of them apparently equal in volume to the main stream. Which is the true Nile? Is it the Blue Nile, which seems to come down from the distant mountains? Or is it the White Nile, which has traversed the immense plains of equatorial Africa. The old Egyptians never knew. The river kept the secret of its source from them as obstinately as it withheld it from us until a few years ago. Vainly did their victorious armies follow the Nile for months together as they pursued the tribes who dwelt upon its banks, only to find it as wide, as full, as irresistible in its progress as ever. It was a fresh-water sea, and sea—iaûmâ, iôma—was the name by which they called it.

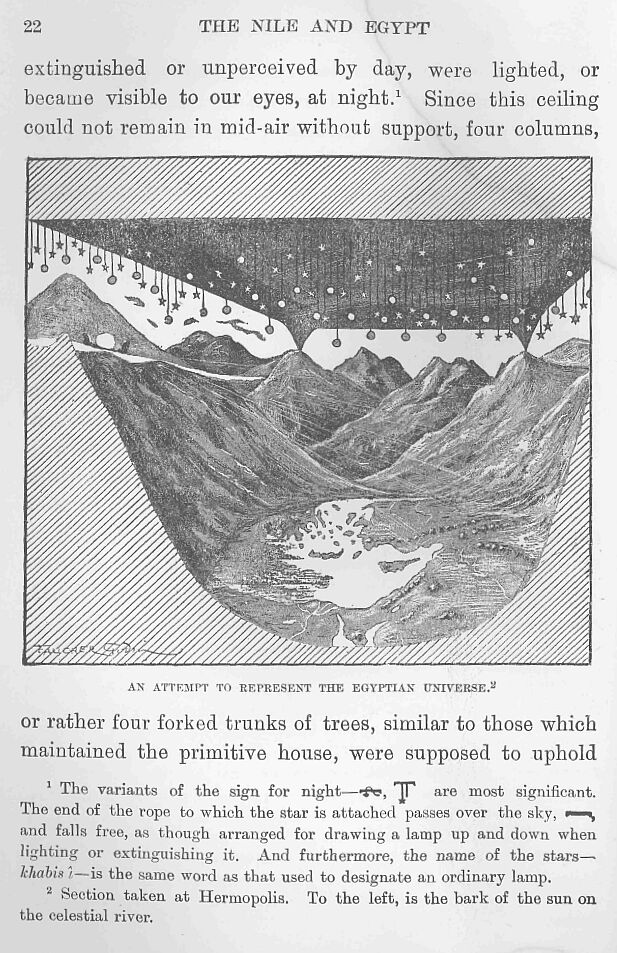

The Egyptians therefore never sought its source. They imagined the whole universe to be a large box, nearly rectangular in form, whose greatest diameter was from south to north, and its least from east to west. The earth, with its alternate continents and seas, formed the bottom of the box; it was a narrow, oblong, and slightly concave floor, with Egypt in its centre. The sky stretched over it like an iron ceiling, flat according to some, vaulted according to others. Its earthward face was capriciously sprinkled with lamps hung from strong cables, and which, extinguished or unperceived by day, were lighted, or became visible to our eyes, at night.

2 Section taken at Hermopolis. To the left, is the bark of

the sun on the celestial river.

Since this ceiling could not remain in mid-air without support, four columns, or rather four forked trunks of trees, similar to those which maintained the primitive house, were supposed to uphold it. But it was doubtless feared lest some tempest should overturn them, for they were superseded by four lofty peaks, rising at the four cardinal points, and connected by a continuous chain of mountains. The Egyptians knew little of the northern peak: the Mediterranean, the "Very Green," interposed between it and Egypt, and prevented their coming near enough to see it. The southern peak was named Apit the Horn of the Earth; that on the east was called Bâkhû, the Mountain of Birth; and the western peak was known as Manu, sometimes as Onkhit, the Region of Life.

Bâkhû was not a fictitious mountain, but the highest of those distant summits seen from the Nile in looking towards the red Sea. In the same way, Manu answered to some hill of the Libyan desert, whose summit closed the horizon. When it was discovered that neither Bâkhû nor Manu were the limits of the world, the notion of upholding the celestial roof was not on that account given up. It was only necessary to withdraw the pillars from sight, and imagine fabulous peaks, invested with familiar names. These were not supposed to form the actual boundary of the universe; a great river—analogous to the Ocean-stream of the Greeks—lay between them and its utmost limits. This river circulated upon a kind of ledge projecting along the sides of the box a little below the continuous mountain chain upon which the starry heavens were sustained. On the north of the ellipse, the river was bordered by a steep and abrupt bank, which took its rise at the peak of Manu on the west, and soon rose high enough to form a screen between the river and the earth. The narrow valley which it hid from view was known as Da'it from remotest times. Eternal night enfolded that valley in thick darkness, and filled it with dense air such as no living thing could breathe. Towards the east the steep bank rapidly declined, and ceased altogether a little beyond Bâkhû, while the river flowed on between low and almost level shores from east to south, and then from south to west. The sun was a disc of fire placed upon a boat. At the same equable rate, the river carried it round the ramparts of the world. Erom evening until morning it disappeared within the gorges of Daït; its light did not then reach us, and it was night. From morning until evening its rays, being no longer intercepted by any obstacle, were freely shed abroad from one end of the box to the other, and it was day. The Nile branched off from the celestial river at its southern bend;[*] hence the south was the chief cardinal point to the Egyptians, and by that they oriented themselves, placing sunrise to their left, and sunset to their right.

* The classic writers themselves knew that, according to

Egyptian belief, the Nile flowed down from heaven. The

legend of the Nile having its source in the ocean stream was

but a Greek transposition of the Egyptian doctrine, which

represented it as an arm of the celestial river whereon the

sun sailed round the earth.

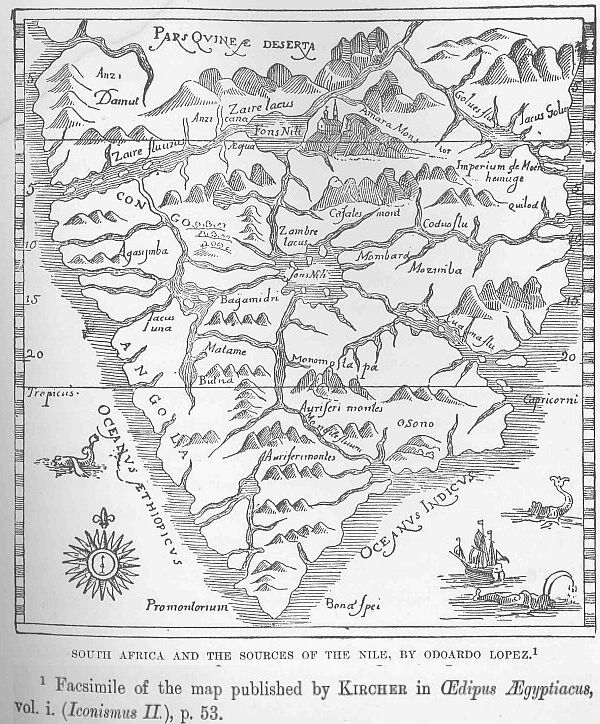

Before they passed beyond the defiles of Gebel Silsileh, they thought that the spot whence the celestial waters left the sky was situate between Elephantine and Philae, and that they descended in an immense waterfall whose last leaps were at Syene. It may be that the tales about the first cataract told by classic writers are but a far-off echo of this tradition of a barbarous age. Conquests carried into the heart of Africa forced the Egyptians to recognize their error, but did not weaken their faith in the supernatural origin of the river. They only placed its source further south, and surrounded it with greater marvels. They told how, by going up the stream, sailors at length reached an undetermined country, a kind of borderland between this world and the next, a "Land of Shades," whose inhabitants were dwarfs, monsters, or spirits. Thence they passed into a sea sprinkled with mysterious islands, like those enchanted archipelagoes which Portuguese and Breton mariners were wont to see at times when on their voyages, and which vanished at their approach. These islands were inhabited by serpents with human voices, sometimes friendly and sometimes cruel to the shipwrecked. He who went forth from the islands could never more re-enter them: they were resolved into the waters and lost within the bosom of the waves. A modern geographer can hardly comprehend such fancies; those of Greek and Roman times were perfectly familiar with them. They believed that the Nile communicated with the Red Sea near Suakin, by means of the Astaboras, and this was certainly the route which the Egyptians of old had imagined for their navigators. The supposed communication was gradually transferred farther and farther south; and we have only to glance over certain maps of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, to see clearly drawn what the Egyptians had imagined—the centre of Africa as a great lake, whence issued the Congo, the Zambesi, and the Nile. Arab merchants of the Middle Ages believed that a resolute man could pass from Alexandria or Cairo to the land of the Zindjes and the Indian Ocean by rising from river to river.[*]

* Joinville has given a special chapter to the description

of the sources and wonders of the Nile, in which he believed

as firmly as in an article of his creed. As late as the

beginning of the seventeenth century, Wendelinus devoted

part of his Admiranda Nili to proving that the river did

not rise in the earthly Paradise. At Gûrnah, forty years

ago, Rhind picked up a legend which stated that the Nile

flows down from the sky.

1 Facsimile of the map published by Kircher in OEdipus

Ægyptiacus, vol. i. (Iconismus II), p. 53.

Many of the legends relating to this subject are lost, while others have been collected and embellished with fresh features by Jewish and Christian theologians. The Nile was said to have its source in Paradise, to traverse burning regions inaccessible to man, and afterwards to fall into a sea whence it made its way to Egypt. Sometimes it carried down from its celestial sources branches and fruits unlike any to be found on earth. The sea mentioned in all these tales is perhaps a less extravagant invention than we are at first inclined to think. A lake, nearly as large as the Victoria Nyanza, once covered the marshy plain where the Bahr el-Abiad unites with the Sobat, and with the Bahr el-Ghazal. Alluvial deposits have filled up all but its deepest depression, which is known as Birket Nû; but, in ages preceding our era, it must still have been vast enough to suggest to Egyptian soldiers and boatmen the idea of an actual sea, opening into the Indian Ocean. The mountains, whose outline was vaguely seen far to southward on the further shores, doubtless contained within them its mysterious source. There the inundation was made ready, and there it began upon a fixed day. The celestial Nile had its periodic rise and fall, on which those of the earthly Nile depended. Every year, towards the middle of June, Isis, mourning for Osiris, let fall into it one of the tears which she shed over her brother, and thereupon the river swelled and descended upon earth. Isis has had no devotees for centuries, and her very name is unknown to the descendants of her worshippers; but the tradition of her fertilizing tears has survived her memory. Even to this day, every one in Egypt, Mussulman or Christian, knows that a divine drop falls from heaven during the night between the 17th and 18th of June, and forthwith brings about the rise of the Nile. Swollen by the rains which fall in February over the region of the Great Lakes, the White Nile rushes northward, sweeping before it the stagnant sheets of water left by the inundation of the previous year. On the left, the Bahr el-Ghazâl brings it the overflow of the ill-defined basin stretching between Darfûr and the Congo; and the Sobat pours in on the right a tribute from the rivers which furrow the southern slopes of the Abyssinian mountains. The first swell passes Khartum by the end of April, and raises the water-level there by about a foot, then it slowly makes its way through Nubia, and dies away in Egypt at the beginning of June. Its waters, infected by half-putrid organic matter from the equatorial swamps, are not completely freed from it even in the course of this long journey, but keep a greenish tint as far as the Delta. They are said to be poisonous, and to give severe pains in the bladder to any who may drink them. I am bound to say that every June, for five years, I drank this green water from the Nile itself, without taking any other precaution than the usual one of filtering it through a porous jar. Neither I, nor the many people living with me, ever felt the slightest inconvenience from it. Happily, this Green Nile does not last long, but generally flows away in three or four days, and is only the forerunner of the real flood. The melting of the snows and the excessive spring rains having suddenly swollen the torrents which rise in the central plateau of Abyssinia, the Blue Nile, into which they flow, rolls so impetuously towards the plain that, when its waters reach Khartum in the middle of May, they refuse to mingle with those of the White Nile, and do not lose their peculiar colour before reaching the neighbourhood of Abu Hamed, three hundred miles below. From that time the height of the Nile increases rapidly day by day. The river, constantly reinforced by floods following one upon another from the Great Lakes and from Abyssinia, rises in furious bounds, and would become a devastating torrent were its rage not checked by the Nubian cataracts. Here six basins, one above another, in which the water collects, check its course, and permit it to flow thence only as a partially filtered and moderated stream. It is signalled at Syene towards the 8th of June, at Cairo by the 17th to the 20th, and there its birth is officially celebrated during the "Night of the Drop." Two days later it reaches the Delta, just in time to save the country from drought and sterility. Egypt, burnt up by the Khamsin, a west wind blowing continuously for fifty days, seems nothing more than an extension of the desert. The trees are covered and choked by a layer of grey dust. About the villages, meagre and laboriously watered patches of vegetables struggle for life, while some show of green still lingers along the canals and in hollows whence all moisture has not yet evaporated. The plain lies panting in the sun—naked, dusty, and ashen—scored with intersecting cracks as far as eye can see. The Nile is only half its usual width, and holds not more than a twentieth of the volume of water which is borne down in October. It has at first hard work to recover its former bed, and attains it by such subtle gradations that the rise is scarcely noted. It is, however, continually gaining ground; here a sandbank is covered, there an empty channel is filled, islets are outlined where there was a continuous beach, a new stream detaches itself and gains the old shore. The first contact is disastrous to the banks; their steep sides, disintegrated and cracked by the heat, no longer offer any resistance to the current, and fall with a crash, in lengths of a hundred yards and more.

As the successive floods grow stronger and are more heavily charged with mud, the whole mass of water becomes turbid and changes colour. In eight or ten days it has turned from greyish blue to dark red, occasionally of so intense a colour as to look like newly shed blood. The "Red Nile" is not unwholesome like the "Green Nile," and the suspended mud to which it owes its suspicious appearance deprives the water of none of its freshness and lightness. It reaches its full height towards the 15th of July; but the dykes which confine it, and the barriers constructed across the mouths of canals, still prevent it from overflowing. The Nile must be considered high enough to submerge the land adequately before it is set free. The ancient Egyptians measured its height by cubits of twenty-one and a quarter inches. At fourteen cubits, they pronounced it an excellent Nile; below thirteen, or above fifteen, it was accounted insufficient or excessive, and in either case meant famine, and perhaps pestilence at hand. To this day the natives watch its advance with the same anxious eagerness; and from the 3rd of July, public criers, walking the streets of Cairo, announce each morning what progress it has made since evening. More or less authentic traditions assert that the prelude to the opening of the canals, in the time of the Pharaohs, was the solemn casting to the waters of a young girl decked as for her bridal—the "Bride of the Nile." Even after the Arab conquest, the irruption of the river into the bosom of the land was still considered as an actual marriage; the contract was drawn up by a cadi, and witnesses confirmed its consummation with the most fantastic formalities of Oriental ceremonial. It is generally between the 1st and 16th of July that it is decided to break through the dykes. When that proceeding has been solemnly accomplished in state, the flood still takes several days to fill the canals, and afterwards spreads over the low lands, advancing little by little to the very edge of the desert. Egypt is then one sheet of turbid water spreading between two lines of rock and sand, flecked with green and black spots where there are towns or where the ground rises, and divided into irregular compartments by raised roads connecting the villages. In Nubia the river attains its greatest height towards the end of August; at Cairo and in the Delta not until three weeks or a month later. For about eight days it remains stationary, and then begins to fall imperceptibly. Sometimes there is a new freshet in October, and the river again increases in height. But the rise is unsustained; once more it falls as rapidly as it rose, and by December the river has completely retired to the limits of its bed. One after another, the streams which fed it fail or dwindle. The Tacazze is lost among the sands before rejoining it, and the Blue Nile, well-nigh deprived of tributaries, is but scantily maintained by Abyssinian snows. The White Nile is indebted to the Great Lakes for the greater persistence of its waters, which feed the river as far as the Mediterranean, and save the valley from utter drought in winter. But, even with this resource, the level of the water falls daily, and its volume is diminished. Long-hidden sandbanks reappear, and are again linked into continuous line. Islands expand by the rise of shingly beaches, which gradually reconnect them with each other and with the shore. Smaller branches of the river cease to flow, and form a mere network of stagnant pools and muddy ponds, which fast dry up. The main channel itself is only intermittently navigable; after March boats run aground in it, and are forced to await the return of the inundation for their release. From the middle of April to the middle of June, Egypt is only half alive, awaiting the new Nile.

Those ruddy and heavily charged waters, rising and retiring with almost mathematical regularity, bring and leave the spoils of the countries they have traversed: sand from Nubia, whitish clay from the regions of the Lakes, ferruginous mud, and the various rock-formations of Abyssinia. These materials are not uniformly disseminated in the deposits; their precipitation being regulated both by their specific gravity and the velocity of the current. Flattened stones and rounded pebbles are left behind at the cataract between Syene and Keneh, while coarser particles of sand are suspended in the undercurrents and serve to raise the bed of the river, or are carried out to sea and form the sandbanks which are slowly rising at the Damietta and Rosetta mouths of the Nile. The mud and finer particles rise towards the surface, and are deposited upon the land after the opening of the dykes. Soil which is entirely dependent on the deposit of a river, and periodically invaded by it, necessarily maintains but a scanty flora; and though it is well known that, as a general rule, a flora is rich in proportion to its distance from the poles and its approach to the equator, it is also admitted that Egypt offers an exception to this rule. At the most, she has not more than a thousand species, while, with equal area, England, for instance, possesses more than fifteen hundred; and of this thousand, the greater number are not indigenous. Many of them have been brought From Central Africa by the river: birds and winds have continued the work, and man himself has contributed his part in making it more complete. From Asia he has at different times brought wheat barley the olive, the apple, the white or pink almond, and some twenty other species now acclimatized on the banks of the Nile. Marsh plants predominate in the Delta; but the papyrus, and the three varieties of blue, white, and pink lotus which once flourished there, being no longer cultivated, have now almost entirely disappeared, and reverted to their original habitats.

The sycamore and the date-palm, both importations from Central Africa, have better adapted themselves to their exile, and are now fully naturalized on Egyptian soil.